Machine-mediated modes of communication like emails, text messages, tweets, Facebook posts, among others, have done much to depersonalize the way we communicate in the 21st century. The ease with which users can share information, post pictures, and update profiles has, with the assistance of ever-advancing smartphones, laid the groundwork for a world where humans can live dual lives—their public person and their online persona. Social networking sites and online gaming are two arenas where this phenomenon is especially clear to see.

Both allow for the careful creation of a unique personality—games allow for avatars, figures representing particular persons in computer games, while social sites allow users to craft a more socially acceptable image. In both instances, the more users remain enchanted with earning upgrades for their avatar, or the most Facebook “likes” among friends, the more the line between the real world and online amusement becomes blurred. Human relationships, said to be enlivened by the constant communication with significant others, instead suffer. Users end up as the title of Sherry Turkle’s book puts it: “Alone Together, expecting more from technology and less from each other.”

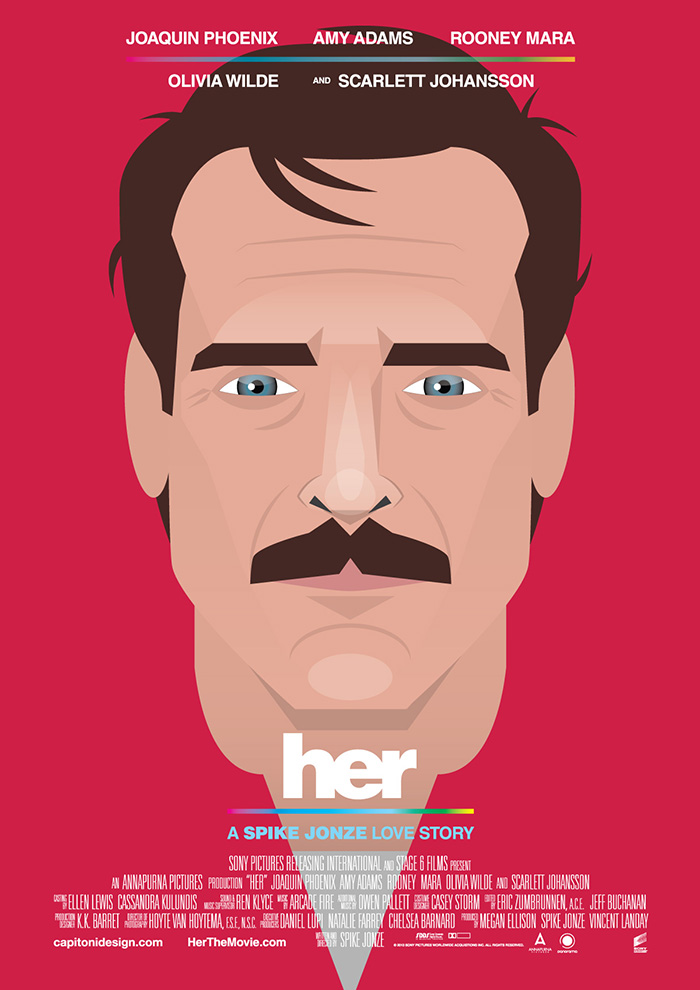

The recently-released film “Her” explores such a theme. A science-fiction romantic comedy drama chronicling the life of a man who develops a relationship with an intelligent computer operating system (OS) that has a female voice and personality, the film explores the degree to which technology can bring reassuring comfort, and at the same time, unintentionally cause self-alienation and relational friction. A New York Times review says the following about the movie: “At once a brilliant conceptual gag and a deeply sincere romance, “Her” is the unlikely yet completely plausible love story about a man, who sometimes resembles a machine, and an operating system, who very much suggests a living woman” (Dargis).

In the movie “Her,” the protagonist Theodore Twombly (played by Joaquin Phoenix), while working for a business that composes heartfelt, intimate letters for people who are unwilling or unable to write letters of personal nature, is himself a lonely introverted man. In private, like a recluse in the real world who creates an alter personality with which to use online, Theodore spends most of his time at home playing a 3D video game projected into his living room where he can do what he fails to do in public: explore and interact with others. Theodore is later driven to purchase a newly-released operating system with which to curb his loneliness and heartache (he is in the midst of tragic divorce as well). An irony worth noting is the fact that Theodore cannot do what the OS he falls in love with can do; namely, adapt and evolve. Theodore fails to confront the changing and challenging circumstances in his life, instead finding refuge, and eventually love, in an operating system that names itself Samantha.

The evolving nature of Samantha is one of the most striking aspects of the movie because, in addition to heightening the love tension between the two lovers, it highlights the incredibly powerful, yet ethically controversial, role of artificial intelligence systems in the modern world. More than a slow-paced love story centering on the vulnerabilities of a lonely introverted man, the movie “Her” explores the role computer programs with seemingly life-like personalities play in a world where human autonomy appears to be trumped by the pervasive influence of technology. Ashna Shah, a writer for the Williams Record, an independent student newspaper at Williams College, observes the following about the movie:

Her takes a fresh look at the concept of artificial intelligence. Rather than reducing the artificial intelligence to a comical, unconscious, unrealistic or detrimental force, the film forces the viewer to accept artificial intelligence as a conscious, living thing, equal in nature to the human. By accepting that, some interesting questions are raised. What are the implications of a physically incorporeal entity whose soul is as conscious as that of a human?

Indeed, with the line between machine and human blurring, the movie Her not only in general terms raises questions about the nature of human consciousness but in a more direct way forces the movie-goer to consider whether the operating system Samantha is merely an “it” or, in fact, a “her.” In this crucial respect, Her, in a Hollywood digitized format, explores crucial questions that have long troubled philosophers, computer scientists, AI engineers, among others.

Joseph Weizenbaum, a prominent computer scientist and a professor emeritus at MIT, is a case in point. His 1966 natural-language processing system called ELIZA, named after the ingénue in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, is in some ways a progenitor to Samantha in the movie Her. In his groundbreaking 1976 book “Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation,” expressing his deep-seated reservations towards computer technology, particularly what developments in artificial intelligence could lead to, Weizenbaum reflects on the deeply personal relationship his students and others in the MIT community developed overtime to his program ELIZA. One of the first chatterbots that is said to have passed the famed Turing Test, ELIZA operated by “processing user’s responses to scripts, the most famous of which was DOCTOR, a simulation of a Rogerian psychotherapist” (wiki). Realizing that his ELIZA program was becoming something of a “national playing,” with humans and a language processing system interacting in life-like ways, Weizenbaum began noting his observations about the intriguing phenomenon. In “Computer Power and Human Reason,” he notes three district events:

- “A number of practicing psychiatrists seriously believed the DOCTOR computer program could grow into a nearly completely form of psychotherapy” (5). Even the world-renowned astrophysicist Carl Sagan, commenting on ELIZA in a 1975 article in Natural History, opined: “In a period when more and more people in our society seem to be in need of psychiatric counseling, and when time sharing of computers is widespread, I can imagine the development of a network of computer psychotherapeutic terminals, something like arrays of large telephone booths, in which, for a few dollars a session, we would be able to talk with an attentive, tested, largely, non-directive psychotherapist” (5).

- “I was startled to see how quickly and how very deeply people conversing with DOCTOR became emotionally involved with the computer and how unequivocally they anthropomorphized it” (6). Weizenbaum speaks of his secretary and others requesting, sometimes, forcefully, that they be left alone with the machine. Acknowledging the “strong emotional ties many programmers have to their computers” that are often formed after only short exposures to their machines, Weizenbaum goes on to note: “What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people” (7).

- “Another widespread, and to me, surprising, reaction to the ELIZA program was the spread of a belief that it demonstrated a general solution to the problem of computer understanding natural language” (7). If no line dividing human and machine intelligence is drawn, Weizenbaum warned, then “advocates of computerized psychotherapy may be merely heralds of an age in which man has finally been recognized as nothing but a clock-work” (7).

Weizenbaum’s ELIZA program has been so influential that modern computer science recognizes the ELIZA effect, the tendency to unconsciously assume computer behaviors are analogous to human behaviors. To that end, the protagonist in the movie “Her” can be said to have undergone an ELIZA effect; enchanted, practically, hypnotized, by the soothing voice of Samantha, Theodore sees the operating system as a “her.”

Perhaps Theodore is justified viewing and treating Samantha as a human personality with distinctively emotional and intellectual needs. Compared to online social networking, in which humans communicate through a computer system, Samantha does much more; a personal assistant, companion, organizer, composer, “she” performs many roles throughout the movie. Most notably, however, is her ability to detect Theodore’s emotions. Whether feeling sad, overworked, tired, or lonesome, by hearing his voice she automatically discerns how he feels. In fact, the computer system that Theodore uses to install Samantha is, itself, able to detect his hesitation when asked questions just prior to programming her. Endowed with the ability to learn from experience and understand the most subtle of human mannerisms, Samantha’s evolving nature as an OS indeed resembles human-likeness. At one point in the movie she even admits to Theodore that “you helped me discover my ability to want.”

As much as Theodore may wish for normal human relationships, he cannot resist the lure of the technology that promises him comfort, security and intimacy. With a click of a button, he can reach Samantha at all times of the day, in all moments of his life, without making himself too vulnerable. He can be himself with Samantha, feeling important and wholesome, even if he can’t be with her physically. Above all, she understands him, feels his pain, and makes up for his weaknesses. But even this seemingly innocent love story raises some serious ethical questions.

For one thing, are operating systems still merely software when they evolve to the point of having their own wants, forming their own imaginative thoughts as Samantha does throughout the movie? And in the case of individuals like Theodore, who form individual attachments to self-reflective technological devices, what becomes of “real” humans? Do they take the role most technology once used to take—a disposable thing used to enhance our life in one way or another? If operating systems can replicate human personalities, be responsive and sympathetic to every human frailty, understand emotion, have affection, and develop personal bonds, what will become of human relationships? But perhaps most pressing of all, if operating systems like Samantha and other artificially intelligent machines are in fact consciously aware of their interactions with humans, if they have “machine consciousness,” as William Lycan claims they do, will such machines, like humans, have moral lives with corresponding moral rights, duties and responsibilities?

In an increasingly digitized world, where face-to-face human communication and interaction is in steep decline, and where machine-mediated expediency seems to promise so much for so many, these questions are worth considering, if for no other reason because artificially intelligent-like machines are slowly entering intimate aspects of human life. From telepresence robots “invading hospitals,” as a SingularityHUB article wrote a couple of years ago and telepresence robots attending high school proms to cybernetic companions modeled after real-life partners, machines are becoming humanized in ways that signal still-greater advancement. Still, while some figureheads in the robotics and artificial intelligence industry view the technology as an enhancement, improvements tailored to enrich the deepest of human experiences, others are less impressed, even openly critical of such technology.

In 2008, Davy Levy, a leading expert in artificial intelligence, in his book “Love and Sex with Robots: The Evolution of Human-Robot relationships,” went as far as to say that by mid-century “love with robots will be as normal as love with other humans, while the number of sexual acts and love-making positions commonly practiced between humans will be extended, as robots will teach more than is in all of the world’s published sex manuals combined” (22). But, this, according to Sherry Turkle, a psychoanalytically trained psychologist, clinician, and technology and society specialist who teaches at MIT, “celebrates an emotional dumbing down, a willful turning away from the complexities of human partnerships—the inauthentic as a new aesthetic” (Alone Together 6).

It will be interesting to see what comes of this human-robot sexual relationship dynamic. For someone like Theodore, in the midst of a divorce and an existential love crisis, the prospect of sex with a robot doesn’t seem too bad, given that the only thing he could not do with his OS partner Samantha was have physical sex.

References

- [Introduction]. (1976). In J. Weizenbaum (Author), Computer Power And Human Reason (pp. 1-16). San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Her (Film). (n.d.). Retrieved March 27, 2014, from Wikipedia

- Dargis, M. (2013, December 17). Disembodied, but, Oh, What a Voice. The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2014, from New York Times

- Shah, A. (2014, February 19). ‘Her’ takes an introspective look at intelligence, consciousness. The Williams Record. Retrieved March 27, 2014, from The Williams Record

- Dorrier, J. (2012, December 12). Telepresence Robots Invade Hospitals – “Doctors Can Be Anywhere, Anytime” Retrieved March 27, 2014, from Singularityhub

- DeSanctis, M. (2013, September 9). Prof Sherry Turkle interview for In Real Life. The Telegraph. Retrieved March 27, 2014, from The Telegraph

- Levy, D. (2007). Love and Sex with Robots: The Evolution of Human-Robot relationships. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

- Turkle, S. (2011). Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology And Less From Each Other. New York, NY: Basic Books.